by Răzvan Balașov, PhD

07.02.2025

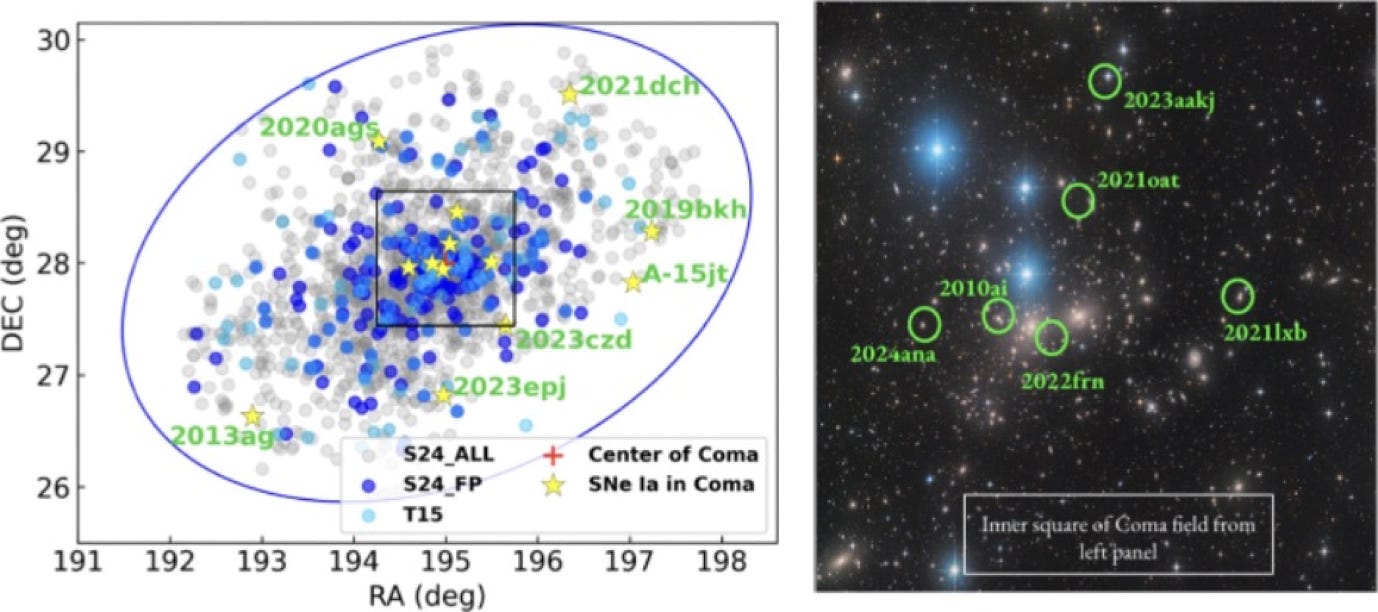

Credit: Vera Rubin Observatory / https://rubinobservatory.org/

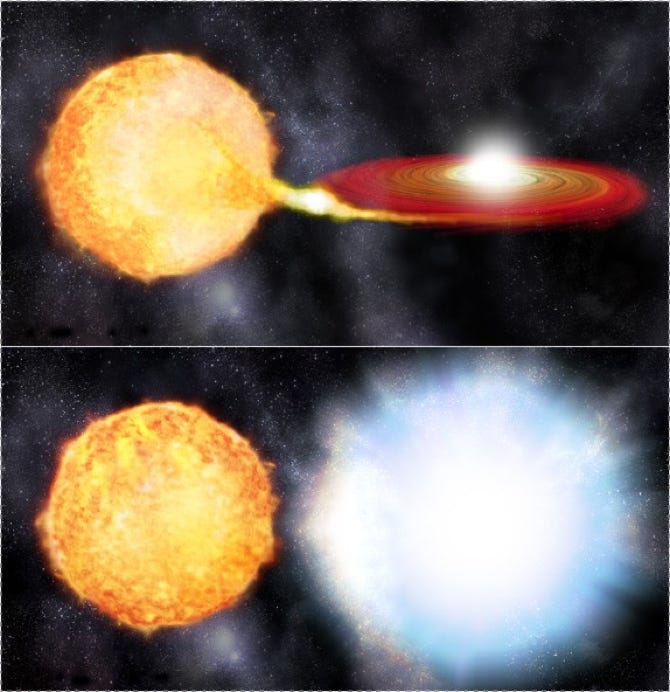

Following last week’s news about a better determination of Hubble’s constant, we must add that other scientific efforts also help in this process. In the near future, the Vera C. Rubin Observatory, a state-of-the-art telescope that is being built in Chile, will transform how astronomers study the expansion of the Universe. Once it will be operational, it will be able to track millions of supernovae (Type Ia) — explosions that occur when white dwarf stars pull in too much material from their companion stars. These supernovae are known as "standard candles" because they shine with a predictable brightness, allowing scientists to measure vast cosmic distances and investigate dark energy, the force driving the accelerated expansion of the Universe.

When the Rubin Observatory begins its 10-year Legacy Survey of Space and Time (LSST), it will collect an enormous amount of data on these stellar explosions, spanning different distances and galaxy types. This data will help researchers refine their understanding of dark energy and determine whether its properties have remained constant over time or have changed.

Astronomer Anais Möller, a member of the Rubin/LSST Dark Energy Science Collaboration, emphasized the importance of this project, noting that Rubin’s vast dataset will allow scientists to study a wide variety of Type Ia supernovae under different cosmic conditions.

By closely analyzing the light from these supernovae, scientists hope to build a clearer picture of how the Universe has expanded over billions of years. The findings could either confirm current cosmological models or reveal new aspects of dark energy that challenge what we think we know about the cosmos.

References: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2025/01/250117161235.htm

https://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.3847/2041-8213/ada0bd#apjlada0bds6

Type I supernova (Credit: NASA/CXC/M.Weiss)