by Valentin Cezar Ionescu

20.02.2026

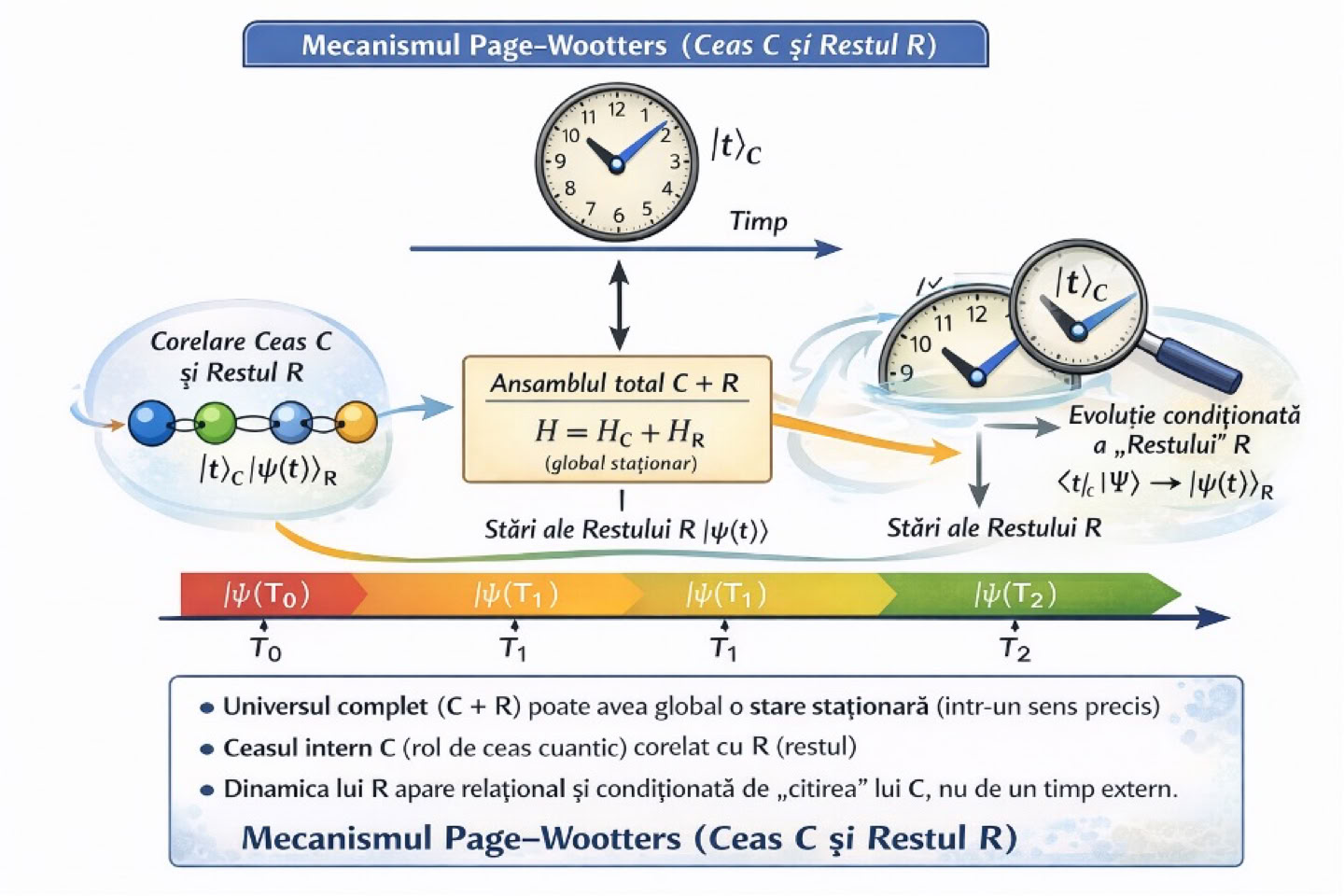

Credit: Educational representation of the Page–Wootters mechanism (Clock C and Rest R).

One of the most difficult questions in modern physics is surprisingly simple: does time exist as we perceive it? In everyday life, time seems obvious - the clock ticks, people age, things change. However, when we try to put together the two great theories of physics (quantum mechanics and general relativity), serious problems arise.

In quantum mechanics, the evolution of a system is described in time: the state changes as time passes. In general relativity, however, time is not a fixed background, but part of the geometry of the universe. In other words, time is no longer just an 'external clock' that flows the same everywhere. When physicists try to quantify gravity, a famous equation (Wheeler-DeWitt) emerges that, in its simplified form, seems to say that the overall state of the universe does not evolve at all. This has sometimes been called the 'frozen formalism': on a global scale, everything seems static, so there is no such thing as time.

But if the universe were globally 'static', how does the change we see occur? This is where the relational idea comes in: perhaps time is not something fundamental, but arises from the relationships between the parts of the system. More precisely, a subsystem can play the role of a clock, and the rest of the system is described in relation to it. So, instead of saying 'what happens at time t' in an absolute sense, we say 'what happens to the system when the clock shows a certain value' [2,4].

This idea was elegantly formulated by Page and Wootters. They propose a universe divided into two parts: a quantum clock (C) and the rest (R). The total state may be stationary (so, from the outside, nothing 'flows' in time), but between C and R there are quantum correlations (entanglement). When we condition the description of R on a certain 'reading' of the clock C, we get a sequence of states that looks exactly like an evolution in time. In short: time can arise from correlations, not necessarily from a fundamental external parameter [3].

The figure shows the central idea of the Page–Wootters mechanism: the total ensemble (Quantum Clock C + Rest R) can be described globally as stationary (without assuming a privileged external time), but for an internal observer using C as a reference, Rest R appears to evolve. This “evolution” is relational: it arises from the correlations (usually entanglement) between C and R and from the conditioning on a reading of the clock. Top (Quantum Clock C). Clock C is represented by a family of states denoted |t⟩_C, which correspond to different “readings”. The “Time” axis suggests that these states can be ordered and used as internal labels t. Important: in this image, t is not an external time imposed on the universe, but a coordinate operationally defined by clock C. Center (Total Ensemble C + R and the Hamiltonian). The central box shows that the "universe" under consideration is bipartitioned into C (the clock) and R (the rest). In the simplified version in the figure, the total Hamiltonian is suggested as H = H_C + H_R. The pedagogical message: at the global level (C+R) we do not introduce from the start an evolution with respect to an external temporal parameter; instead, the relevant “time” will be that defined by the internal clock C. Left (Correlation between C and R). The bubble on the left emphasizes that C and R are not independent: correlations of the form |t⟩_C ⊗ |ψ(t)⟩_R appear. Intuitively, for each possible reading of the clock C, the rest of R is associated with a corresponding state |ψ(t)⟩_R. A schematic writing of the idea is that the global state can be seen as a superposition of such “correlated pairs”: |Ψ⟩ ≈ Σ_t |t⟩_C ⊗ |ψ(t)⟩_R (where the sum can also be an integral, as the case may be). Right (Conditional evolution of R). On the right is the key step: if we “fix” a clock reading (e.g., the clock indicates t), then the description of R becomes the conditional state obtained by projection onto C. The formula in the figure, ⟨t|_C |Ψ⟩ → |ψ(t)⟩_R, expresses just this. From the perspective of an internal observer using clock C, the dependence of R’s state on t is interpreted as the dynamics of R. Bottom (State sequence of R). The bottom colored bar represents the “movie” of R’s conditional states: at clock reading T0, R is in |ψ(T0)⟩_R; at clock reading T1, R is in |ψ(T1)⟩_R; at clock reading T2, R is in |ψ(T2)⟩_R, etc. The visual conclusion is that an apparently temporal sequence of R’s states can arise from the correlation with C, even if the global description of the ensemble C+R is stationary.

An important point is that this idea did not remain only philosophical. Moreva et al[1] performed an experiment with two entangled photons to illustrate the Page-Wootters mechanism. One photon was treated as a 'clock', the other as a 'system'. Depending on how the experiment is viewed, two perspectives emerge: for an 'internal' observer, who uses one of the photons as a reference, the other appears to evolve; for a 'super-observer', who has access to the global properties of the pair, the total state remains practically unchanged.

The result is interesting because it operationally shows something profound: the same quantum reality can appear dynamic from the inside and static from the outside, without contradiction, if we take into account the role of correlations and the way in which we make the measurement. Moreover, extensions of the idea show that when the clock is imperfect (as all real clocks are), limitations and decoherence effects appear - that is, a decrease in the clarity of the observed evolution.

It is essential to be rigorous in our conclusions. The experiment does not 'solve' the problem of time in quantum gravity. It does not quantify gravity itself, and it does not reproduce the entire mathematical structure of quantized general relativity. What it does do, however, is very valuable: it provides a laboratory demonstration that the idea of time emerging from quantum correlations is coherent and can be tested in controlled systems.

Perhaps time, as we experience it, is not a fundamental component of the universe, but a phenomenon that arises from the way in which the parts of the universe relate to each other. It is a radical but perfectly legitimate idea in modern physics, and one of the ways in which researchers are trying to understand how quantum mechanics and gravity fit together. In the long run, such ideas are relevant to very big questions: what happens near black holes, how we describe the very early universe, and what a complete theory of quantum gravity would look like. Even though the photon experiment is simplified compared to the real universe, it has enormous value as a conceptual model: it shows that our intuitions about time can be tested step by step, not just discussed abstractly.

References:

[1] E. Moreva et al., „Time from quantum entanglement: an experimental illustration”, arXiv:1310.4691 (2013); Phys. Rev. A 89, 052122 (2014).

[2] B. S. DeWitt, „Quantum Theory of Gravity. I. The Canonical Theory”, Phys. Rev. 160, 1113–1148 (1967).

[3] D. N. Page, W. K. Wootters, „Evolution without evolution: Dynamics described by stationary observables”, Phys. Rev. D 27, 2885 (1983).

[4] K. V. Kuchař, „Time and interpretations of quantum gravity”, în: Proceedings of the 4th Canadian Conference on General Relativity and Relativistic Astrophysics, ed. G. Kunstatter, D. Vincent, J. Williams (World Scientific, Singapore, 1992).