by Răzvan Balașov, PhD

A new observational study hints at how big (from a mass point of view) can black holes grow. This is the

latest of several attempts during the past (ref 1, ref 2, ref 3)

The current paradigm is that a category of these objects (massive and supermassive ones) lies in the

centers of galaxies. Observations and estimations place the most massive of them at mass values of tens

or even a hundred billion solar masses. Therefore, a new keyword was introduced: ultramassive

(simplified as UMBH or UBH), for massive black holes that exceed 10 billion solar masses - although the

value is still disputed. For reference, massive black holes (MBHs) start somewhere at tens of thousands

of solar masses and supermassive ones (SMBHs) at hundreds of thousands.

A popular method to determine the mass of a black hole is to link it to the stellar mass of their host

galaxies (scaling relations). These correlations also suggest that there is a tight connection between the

formation of stars and central black hole growth. Thus, the higher the stellar mass of a galaxy, the

“bigger” the black hole can get.

A team led by Priyamvada Natarajan from the Department of Astronomy at Yale University suggests that

there should be a limit for this growth and that limit is imposed by the black hole itself. Considering that

black holes cannot accrete the entire available material that surrounds them and that this material has

to be relatively close to the object, a few growth-related difficulties pop into discussion.

Firstly, massive black holes generate astrophysical jets of particles from the gas, dust, and stars that is

not accreted. This action prevents star formation around the central black hole (gas and dust need to

clump together in order to form stars and that can happen only if they cool down).

Secondly, this generation of particle jets also pushes the available gas that was near the black hole (the

central region of the galaxy). And, once this central region material is consumed, the black hole growth

stops.

Considering these factors, Natarajan places the upper mass limit around 100 billion solar masses.

Momentarily, this statement is supported by their latest finding, Phoenix A, which lies approximately at

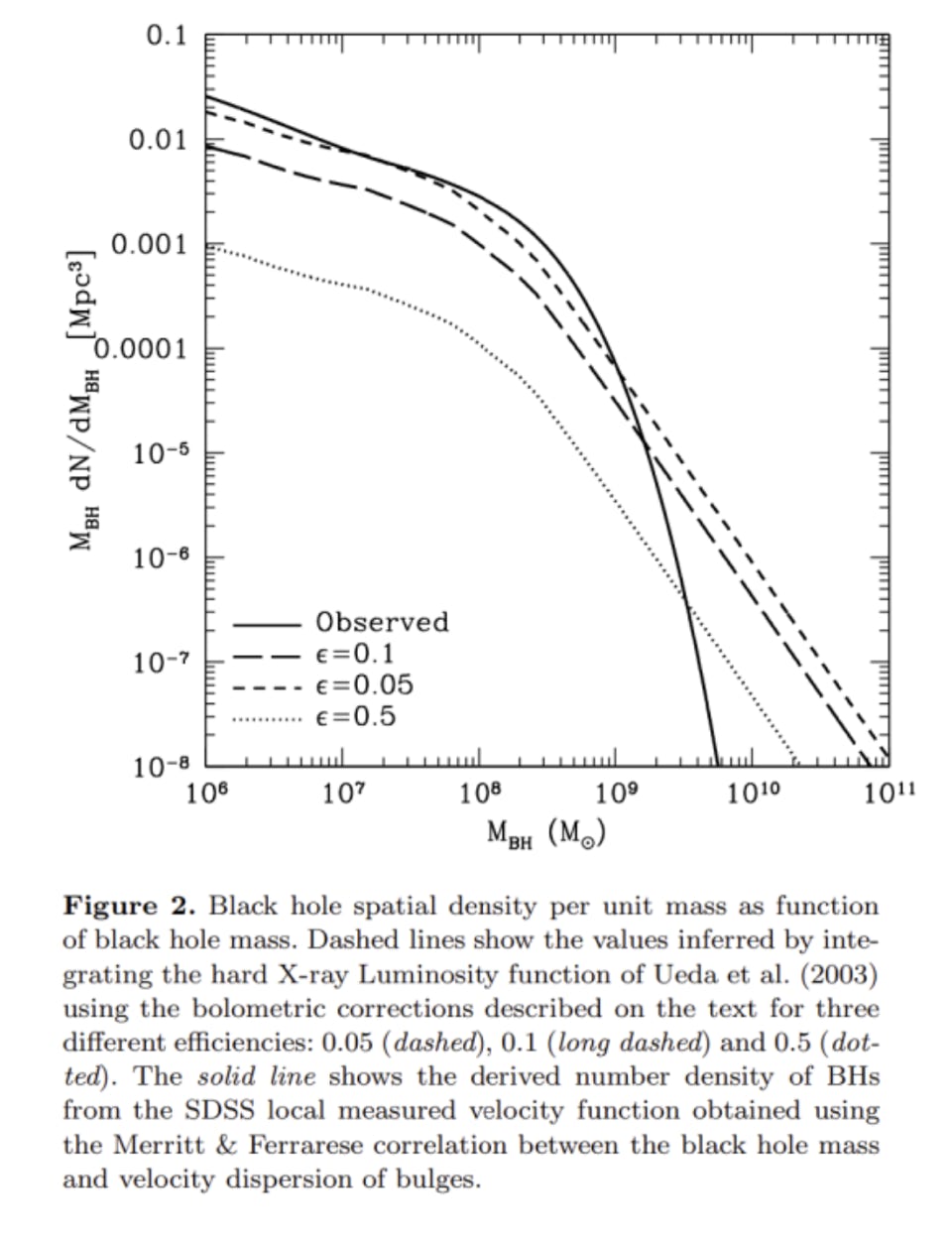

that value limit. You can check out the following figure for more details on the observed and predicted

black hole mass depending on the different efficiencies (epsilon) with which the black hole accretes

material:

The team's research is published on the scientific preprint repository site arXiv.